A Decade of Stops & Starts: Kitsap Transit, 2003-2013

This is Part Three of our series of stories examining the history of Kitsap Transit. You can read Part One here and Part Two here.

On Sept. 19, 2003, Washington State Ferries officially ended its passenger-only fast ferry service between Bremerton and Seattle.

In that day’s Kitsap Sun, ferry riders lamented the soon-to-be-shuttered service, which had carried commuters between Kitsap County and Seattle for more than 10 years. The State Transportation Commission voted the previous year to cut the service after years of debate and litigation over the impact of vessel wakes in Rich Passage.

The reporter offered this epitaph: “(The last ferry run is) the requiem for any hope the state will ever provide passenger service again, much less expand to Kingston or Southworth.”

Instead, that responsibility fell to Kitsap Transit, which inherited from Washington State Ferries (WSF) a federal research grant to study wake damage in Rich Passage.

“(Representative Norm Dicks) called and said the state was looking for someone to pick up the grant,” former Kitsap Transit Executive Director Dick Hayes said. “I thought we needed it.”

The 2000s were a tumultuous decade for Kitsap Transit – bracketed on each end by the passage of I-695 and a generational recession, both of which forced service cuts and downsizing. In between, the agency twice asked voters to approve funding for a new passenger-only fast ferry program to Seattle. Twice, voters rejected the measure.

But there was also progress and growth: The agency moved into new offices on the top floors of a new conference center; designed, built and tested an experimental research vessel; partnered with Puget Sound Naval Shipyard to replace its Worker/Driver bus fleet; and joined a regional network of transit agencies that debuted a new fare card (ORCA).

A new home for transit

Before the turn of the century, Kitsap Transit’s bus system was constrained by the lack of space at the old ferry terminal. As a result, the East Side and West Side routes were forced to alternate departures and arrivals on the half-hour and quarter-hour.

The new Bremerton Transportation Center, completed in 2000, provided enough space for extra buses to accommodate increasing passenger demand, plus a covered waiting area and a new customer service office on the same level as the entrance to the ferry terminal.

“That helped a lot by getting our customer service right where a major hub of the transit system (was),” Kitsap Transit Executive Director John Clauson said.

The newly rebuilt transit center was followed several years later by the Harborside facility, the first of several large projects aimed at remaking downtown Bremerton. As part of the $47 million project – which also included the Kitsap Conference Center and a hotel – Kitsap Transit built two floors of new offices on top of retail space. The agency moved into its new offices in 2004.

A history of fast ferries in the Puget Sound

In 2003, Kitsap Transit found itself in the thick of a decade-long debate over passenger-only ferry connections between Kitsap County and Seattle.

Before that, throughout the 1990s, WSF ran a popular passenger-only ferry service from Bremerton to Seattle. The trips were quick, about 30 minutes, outpacing the slower car ferries. However, the ferries that operated the route produced large wakes that damaged the beaches and bulkheads of property owners who lived on Rich Passage.

“Almost immediately, residents started complaining about those first few ferries,” said Alice Tawresey, who chaired the state Transportation Commission in the early 1990s.

As a Bainbridge Island resident, Tawresey was a big proponent of alternative connections to King County. A 30-minute fast ferry would put Bremerton’s service on par with Bainbridge’s.

“Mostly the people that live in Bremerton work in Bremerton,” Tawresey said. “Having a less expensive alternative than a big 100-car, 200-car ferry just for passengers made sense.”

The commission, which oversaw WSF and the state highway system, recommended expanding the foot ferry system in 1993. Voters even passed a measure to fund the expansion in 1998.

The first wave of ferries that operated the service in the early ‘90s – the Tyee, Skagit and Kalama – gave way to a second generation of vessels designed to minimize wake impacts. Those vessels – the Chinook and the Snohomish – were forced to slow down after shoreline property owners sued the state Department of Transportation in 1999.

Following the passage of I-695 at the turn of the century and the loss of revenue from Motor Vehicle Excise Taxes, the state pulled the plug on the ferry program for good.

“They had to cut the budget somewhere, and since the passenger-only ferries weren’t working out – not that many people were taking them, and there was all this dispute about the shoreline – they stopped running them,” Tawresey said.

The search for a solution

For years, Kitsap Transit operated buses that directly fed the ferry terminals in Bremerton and Bainbridge Island. But a more direct connection to Seattle began with the end of WSF’s passenger-only ferry program. The agency inherited a federal research grant from WSF to study wakes in Rich Passage, and legislators passed a bill allowing Kitsap Transit to form a special taxing district to fund the service.

After WSF’s operation ended, Kitsap Transit turned around and quickly put a ballot measure out to voters in the November 2003 election, which would have raised sales taxes and motor vehicle excise taxes to pay for a new fleet of fast ferries. It was soundly defeated.

“My personal opinion is the fact that we could not guarantee that we could run high-speed (led to the vote failing),” Clauson said. “The state tried it and had to slow down – what makes you think you could do it?”

Hayes, however, continued to champion the idea. With support from federal legislators, Kitsap Transit’s challenge was to find a boat that could make the run worth it – fast enough to offer commuters tangible time savings, while not damaging the beaches of Rich Passage.

While the agency studied the wake impact of several different vessels, it tried again to get voters to sign on to the plan in 2007. This time, Kitsap Transit had partnered with a private operator to run fast ferries to Seattle, but the measure failed again.

“People couldn’t see enough distinctiveness between the fast boats and the big, slow boats,” Hayes said.

All the while, Kitsap Transit was studying the beaches of Rich Passage. With the help of federal funding secured by Rep. Norm Dicks and Sen. Patty Murray, the agency designed and built an experimental foil-assisted ferry: the Rich Passage 1.

The vessel, based on a design from Teknicraft in New Zealand and built by All-American Marine in Bellingham, wasn’t an immediate success. The experimental foil meant to reduce the amount of hull in the water fell off several times during testing.

What was clear was the science: After several months of testing in 2012, the marine engineering firm running the study confirmed that the ferry wasn’t damaging the beaches. It would be several years before fast ferries returned to Bremerton, but by the start of 2013, Kitsap Transit knew it had the right vessel.

“The (Rich Passage 1) was the key to everything,” Hayes said. “The design was right. We knew we needed a leap forward.”

Weathering the storm: The Great Recession

In early 2000, the Legislature passed a law repealing the state Motor Vehicle Excise Tax, a major revenue stream for most transit agencies in Washington, including Kitsap Transit. Kitsap County voters approved a local sales tax increase in 2001 to recoup most, but not all, of the lost revenue.

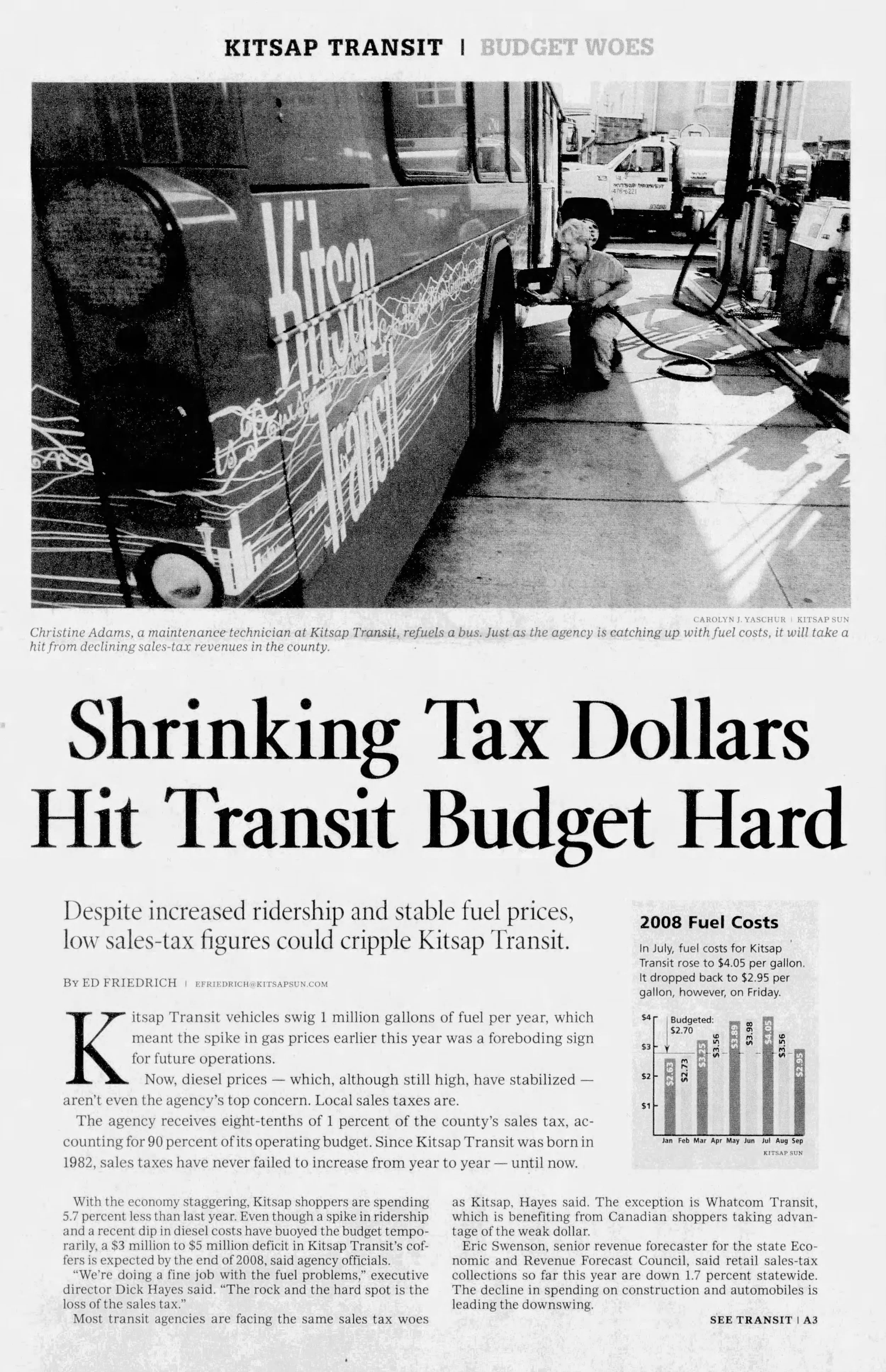

That meant that by 2008, at the onset of the global recession, Kitsap Transit was chiefly dependent on sales tax for its revenue.

“When the economy went south, people stopped spending money. The revenue stream dropped significantly and we didn’t have any choice,” Clauson said. “We had to make adjustments to live within that new revenue stream.”

Fluctuating fuel prices forced Kitsap Transit to make service cuts in early 2008, and things got worse as sales tax revenues plummeted. The agency laid off employees, raised fares and drastically cut service – including Sunday service – at a time when more and more people were starting to ride transit.

Cutting Sunday service was an unpopular decision. But at the time, Kitsap Transit had to make decisions quickly to stay afloat, Clauson said. In addition to being the day with the lowest ridership, cutting one entire day of service allowed Kitsap Transit to save service hours during the rest of the week. Most of the savings came from maintenance and supervisory expenses.

“We did what we had to do. It was painful, but I think the decisions that we made were correct. The decision of Sunday, for example, I think as painful as that was, was probably one of the best decisions on how to respond to that,” Clauson said.

Sunday service wouldn’t be restored until 2023, but Kitsap Transit as an agency learned some valuable lessons from the recession. After taking over the Executive Director role in 2012, Clauson implemented a fuel stabilization fund and beefed up the agency’s reserves.

“I'm hopeful that based on what we've done here, if that ever happens again, we can be more thoughtful on how we make changes,” Clauson said.

Passing the torch

It wasn’t all doom and gloom. Ridership grew to a high of 5.4 million in 2008. In 2011, Kitsap Transit worked with the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard to add a $15 surcharge to shipyard employees’ transportation passes, which funded replacement buses for an aging Worker/Driver fleet.

Up until that point, the Worker/Driver program was made up mostly of hand-me-down coaches from Kitsap Transit’s routed fleet. The new buses were “over the road” style – larger and more comfortable, with reclining seats, luggage racks and individual reading lights.

“The quality of the ride was much better,” Clauson said.

In 2009, seven transit agencies around Puget Sound debuted the One Regional Card for All, or ORCA. The new “smart card” promised to modernize fare payment and make it possible to transfer more easily between transit agencies.

Finally, at the end of 2012, Kitsap Transit said goodbye to Dick Hayes, who had been the agency’s first and only executive director up to that point. After a nationwide search, Kitsap Transit’s Board of Commissioners picked Clauson as Hayes’ successor.

Clauson called Hayes a “visionary” who helped shepherd Kitsap Transit through its early years. Hayes wrote many of Kitsap Transit’s plans himself, helped educate the community and a brand-new board of commissioners, pushed for paratransit and fast ferry services, and was a tireless advocate for public transit in Kitsap County.

“He is probably one of the smartest people that I’ve ever known,” Clauson said. “Kitsap Transit wouldn’t be the agency it is today without Dick Hayes.”